This post is about some of the intuition behind the theorem of Gaussian Isoperimetric Inequality that I have.

Isoperimetric Inequality and $\epsilon$-extension

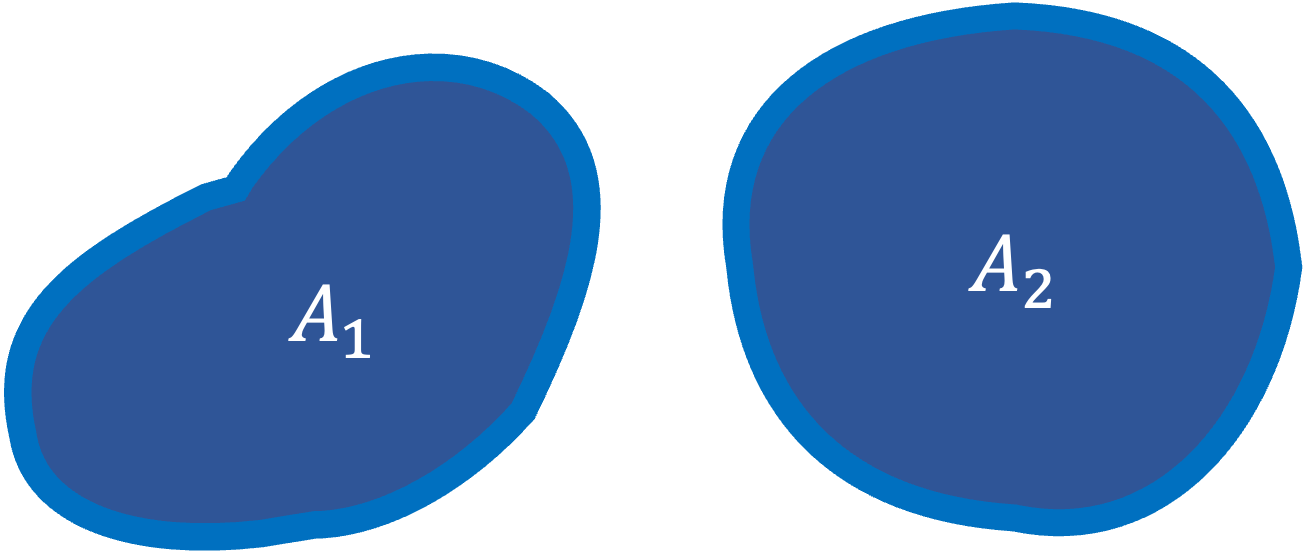

Before considering the Gaussian measure, we begin with something simpler. As the word $\textit{isoperimetric}$ implies, let us imagin that we have two strings that are identical in perimeter, i.e., equal in length, and think about making shapes by enclosing them. Countless shapes can be made, but which of them maximizes the area enclosed by the string?

It is a circle, $A_{2}$. I don’t think this is necessarily obvious to everyone, and in fact, I would say I believed it more than I understood it, but I managed to convince myself with the Wikipedia explanation that a drop of water becomes a sphere.

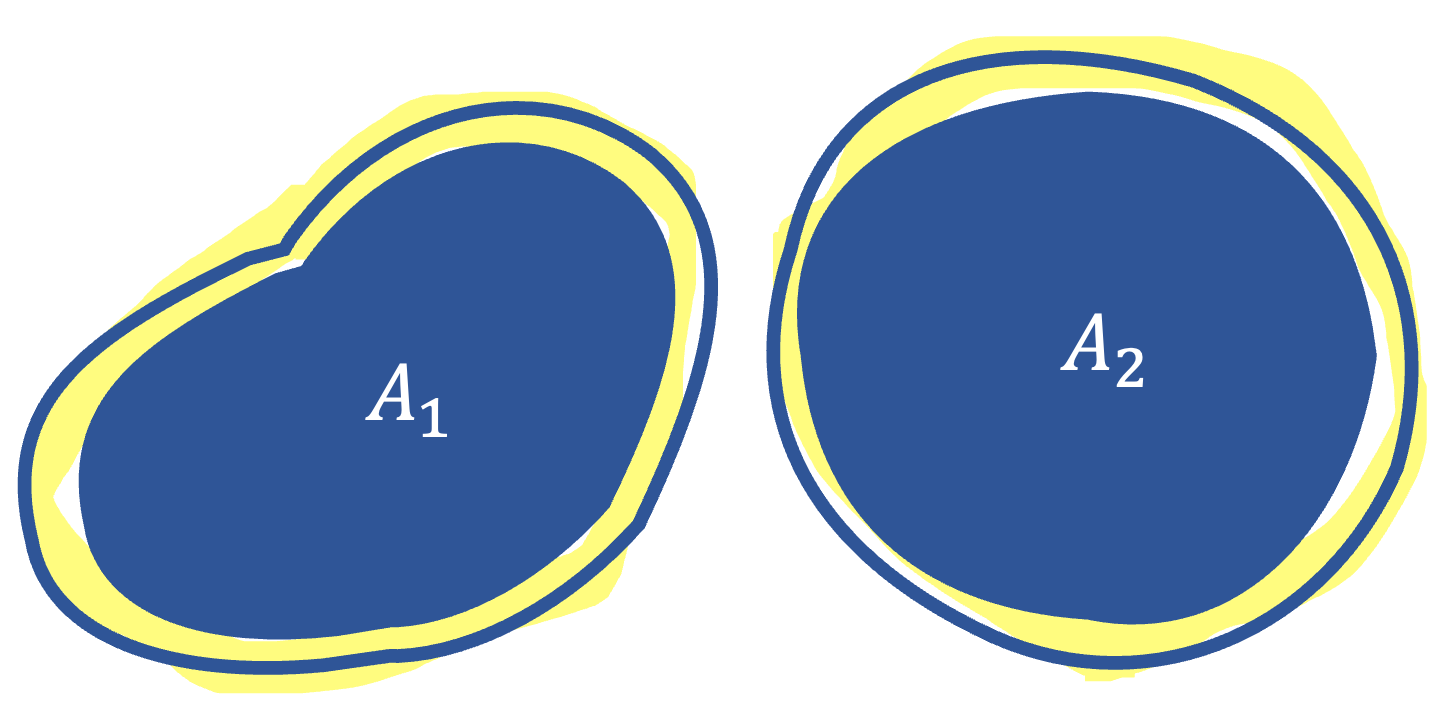

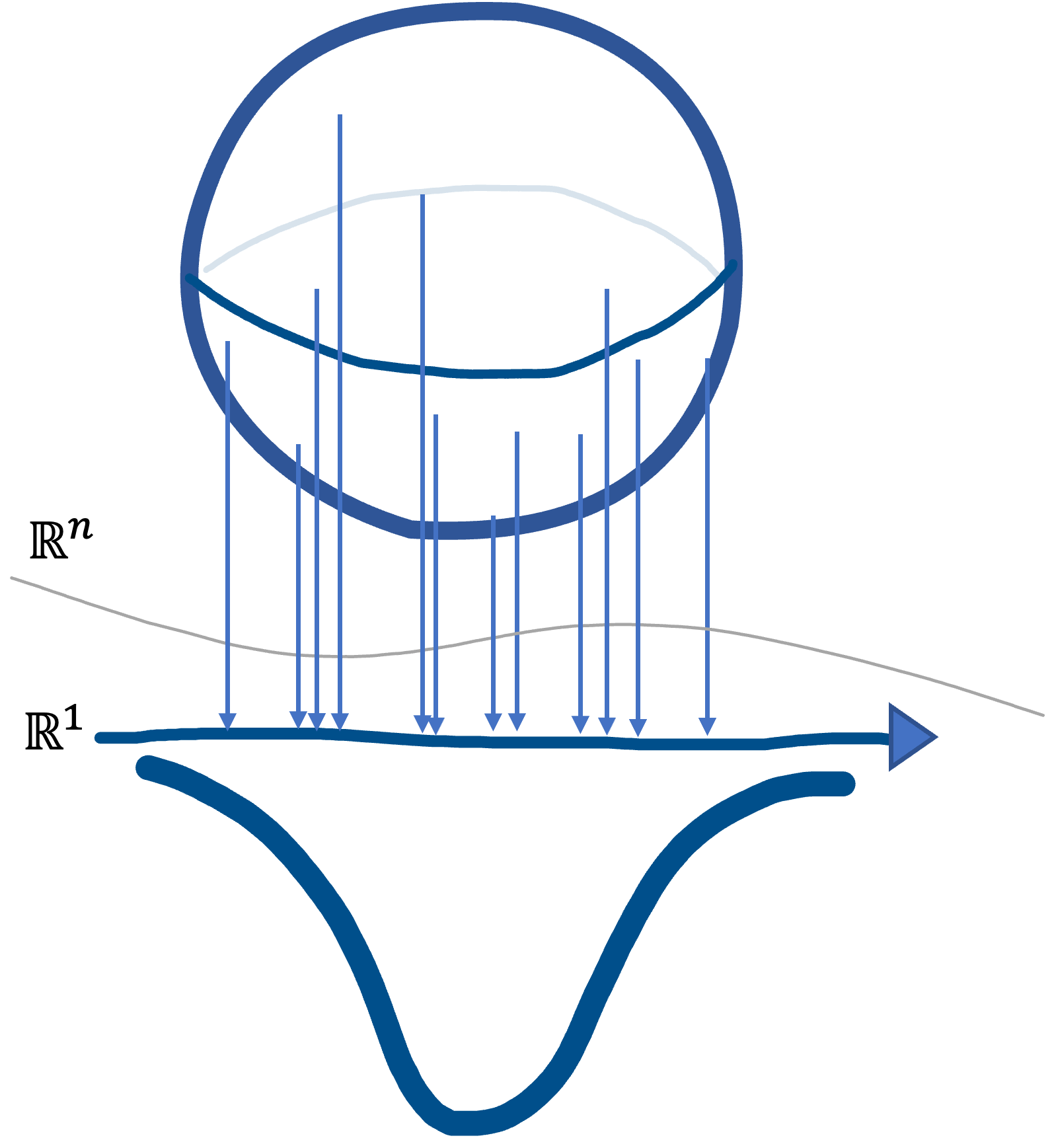

We fixed the length of the strings in this example, but now we assume that the strings are stretchable, and instead, we fix the area inside the enclosure; I mean $\mu(A_{1}) = \mu(A_{2})$, where $\mu(A)$ is the area of $A$. In this case, which length of the string is shorter, $A_{1}$ or $A_{2}$? If the water drop story makes sense to us, then no surprise about this, it is $A_{2}$, saying that if the areas are equal, the perimeter will be the smallest when forming a circle. Let us express this a little more formally. The perimeter is defined as \[ \text{surf}(A) := \liminf_{\epsilon \rightarrow \infty}\ \frac{\mu(A_{\epsilon}) - \mu(A)}{\epsilon}. \] We introduce the notion of $\epsilon$-extension, and the $\epsilon$-extension of $A$ is denoted by $\mu(A_{\epsilon}$, which is defined as \[ A_{\epsilon} =\{ x: d(x, A) \leq \epsilon \} \] where $d(x,A)$ denotes the distance from $x$ to the nearest point in $A$. It is just saying that $A_{\epsilon}$ is $A$ blown up by a small $\epsilon$, like below.

The isoperimetric inequality says $\text{surf}(A_{1}) \geq \text{surf}(A_{2})$.

In Gaussian measure

Instead of the area $\mu$ earlier, we consider the gaussian measure $\gamma$.

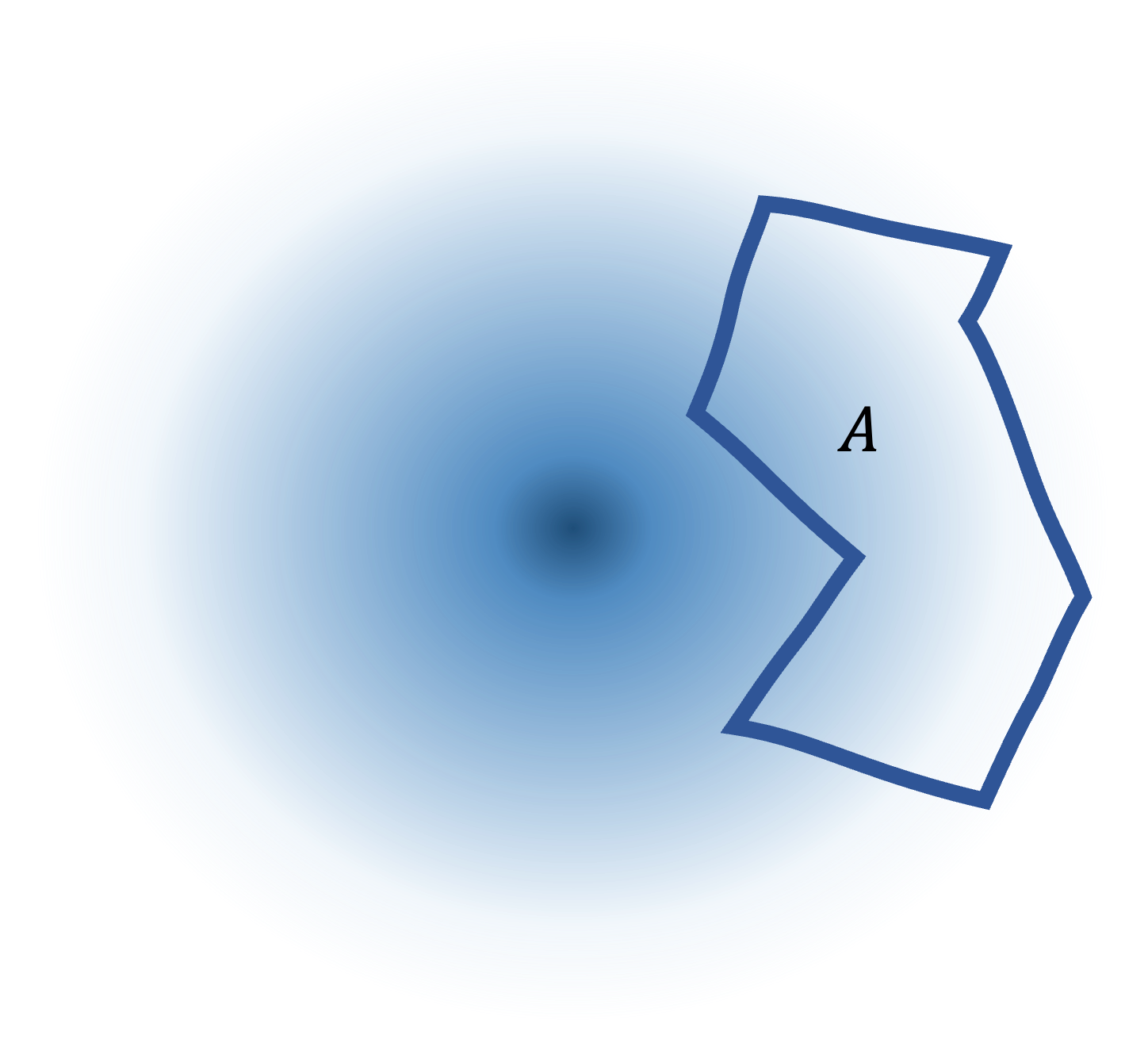

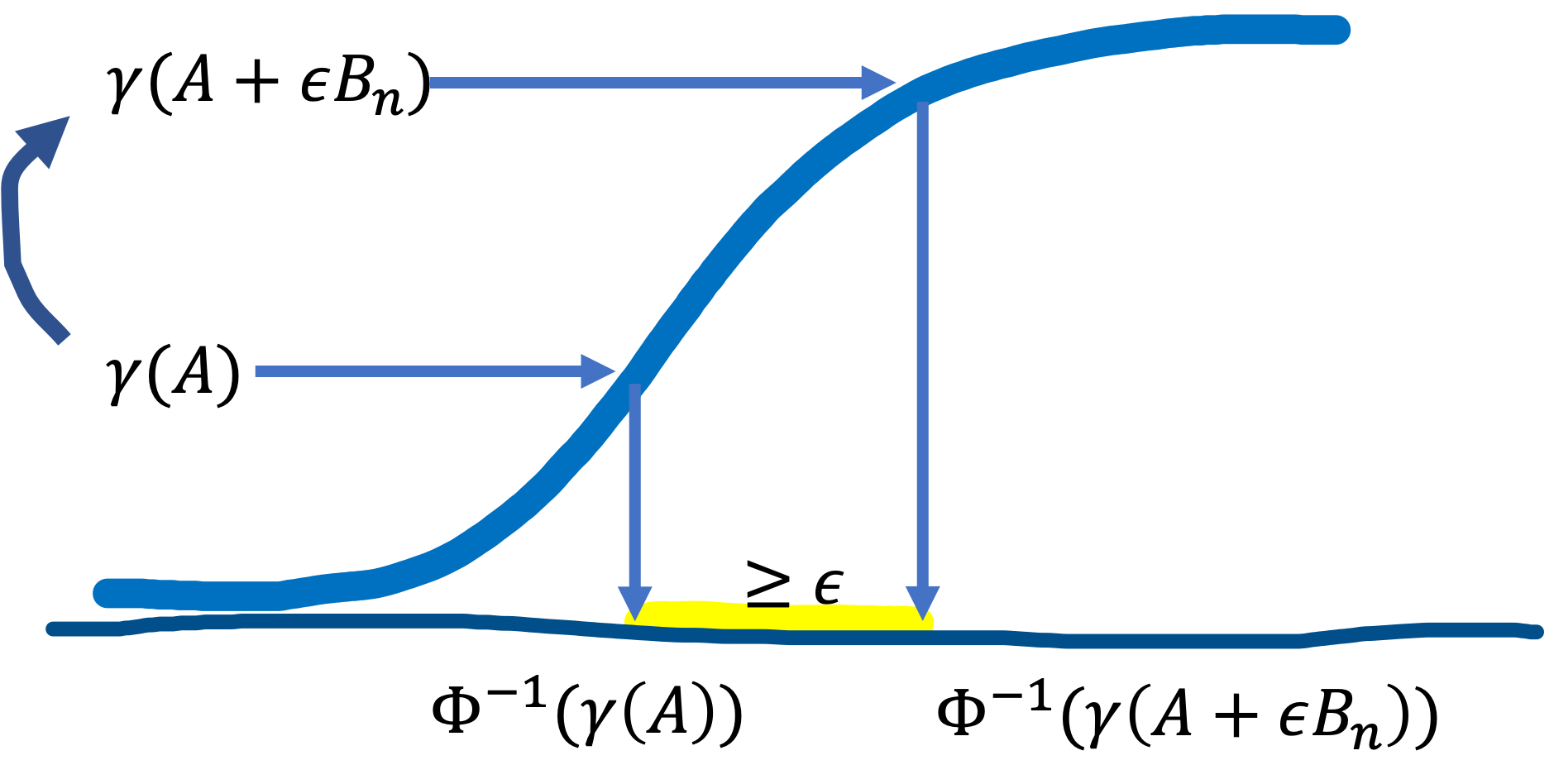

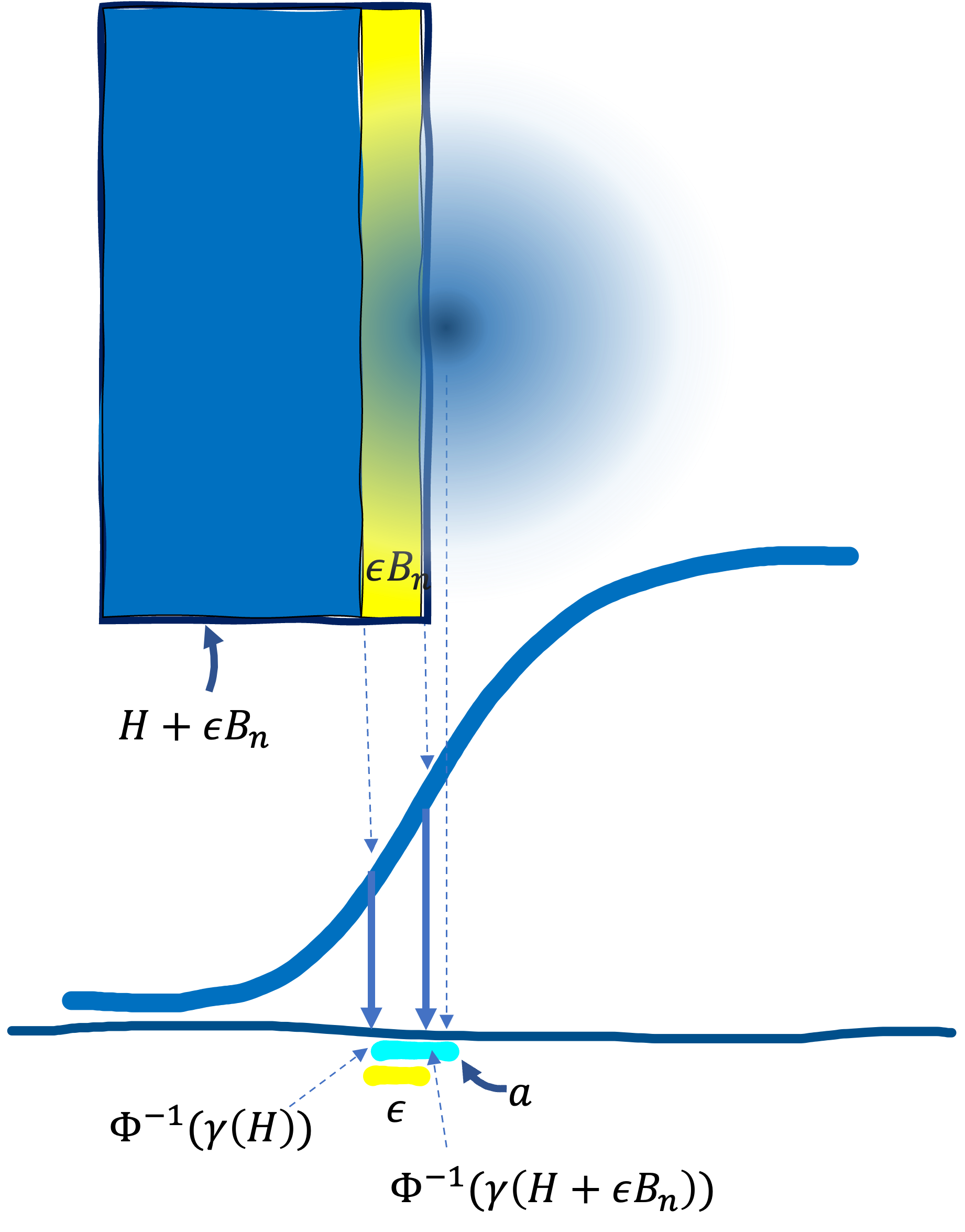

$\gamma(A)$ is something like the density assigned to the entire region $A$ in the Gaussian distribution in $n$-dimensional space. The closer $A$ is to the mean, the larger $\gamma(A)$ becomes. We express $\epsilon$-extension of $A$ as $A_{\epsilon} = A + \epsilon B_{n}$, where $B_{n}$ is an unit ball in $n$ dimension space. $\epsilon$-expansion can be thought of as covering $A$ by a huge number of tiny balls, or hyperspheres, with radius $\epsilon$ centered on every point of $A$. Then, Gaussian isoperimetric inequality says \[ \Phi^{-1} ( \gamma(A + \epsilon B_{n})) \geq \Phi^{-1} ( \gamma(A)) + \epsilon, \label{eq:1}\tag{1} \] where $\Phi$ is the CDF of Gaussian. It is saying that $\epsilon$-extension of $A$ makes the yellow line longer than $\epsilon$ in the following.

We saw that, when $A \subset \mathbb{R}^{2}$ is a circle, the length of the string is the shortest, which means that the variation due to $\epsilon$-extension is minimum. We consider a case where $A$ is the half space $H = \{ x \in \mathbb{R}^{n}: \langle x,u \rangle \leq a \}$ in Gaussian measure, where $u$ is a unit vector, along which $H$ is aligned, and $a$ is the cutoff level of the projection onto $u$. Then, the change due to $\epsilon$-extension is minimum for $H$ among all $A$, i.e., $\gamma(A + \epsilon B_{n}) \geq \gamma(H + \epsilon B_{n})$ for all $A$.

It is difficult to get an intuition as to all this, but let me leave this for now and move on. We show that when $A = H$, the equality holds in Eq.$\,$($\ref{eq:1}$), i.e., \[ \Phi^{-1} ( \gamma(H + \epsilon B_{n})) = \Phi^{-1} ( \gamma(H)) + \epsilon. \] Here, we use the property that an orthogonal projection of a multidimensional Gaussian into one dimension becomes a $1$-dimensional Gaussian.

Thus, the $\epsilon$-extension of $H$, $H_{\epsilon}$, is expressed using $\Phi$ as shown in the figure below.

We apply an $\epsilon$-expansion to the whole boundary of $H$, but portions other than the depicted slice are events at infinity and can be dismissed. Since $H_{\epsilon}$ can be writen as $H_{\epsilon} = \{ x \in \mathbb{R}^{n}: \langle x,u \rangle \leq a + \epsilon \}$ and $\Phi^{-1} ( \gamma(H)) = a$, \[ \Phi^{-1} ( \gamma(H + \epsilon B_{n}) = a + \epsilon = \Phi^{-1} ( \gamma(H)) + \epsilon. \] Thus we know that if $A=H$, then the equality holds in Eq.$\,$($\ref{eq:1}$).

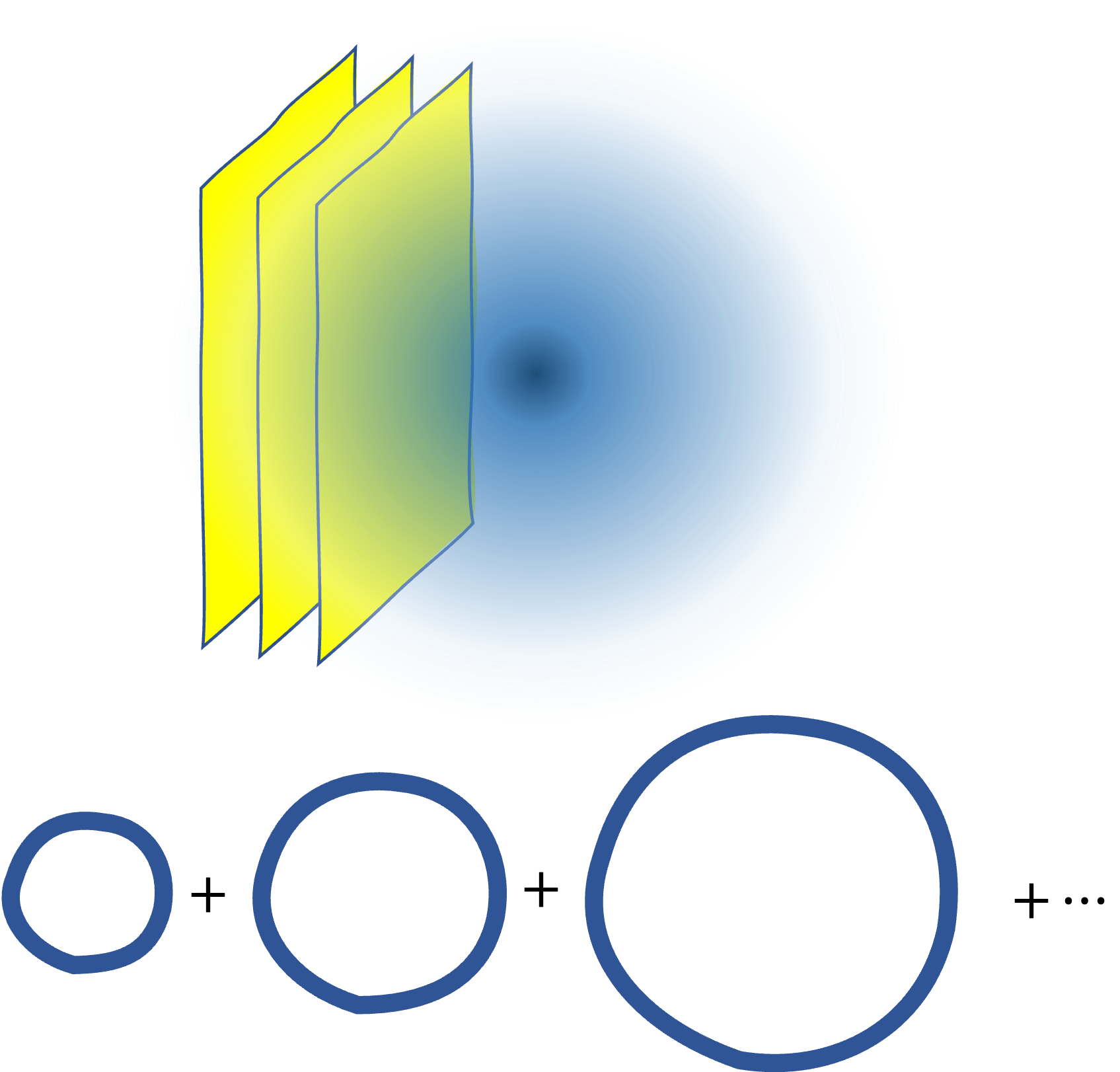

Finally, I would like to address what I have postponed: why $\gamma(A) \geq \gamma(H)$. I honestly can’t say it’s crystal clear to me… but, based on what we saw in Isoperimetric Inequality, we can develop the following intuition: Let us view $A$ as a set of slices. If $A$ is a half space, then every cross-section of $A$ is Gaussian.

Considering the Gaussian as a circle or a set of countless concentric circles, then the measure of the whole $A$ will be minimized. If $A$ is not a half space, then some cross-sections are inefficiently increasing its measure, resulting in $\gamma(E) \geq \gamma(H)$.